Check Point Software and Cato Networks Co-Founder Shlomo Kramer Shares His Journey: From ‘Firewall-1’ Software to Today’s Firewall as a Service

By: Shlomo Kramer, Check Point Software & Cato Networks Co-Founder

By: Shlomo Kramer, Check Point Software & Cato Networks Co-Founder

As one of the founders of Check Point Software and more recently Cato Networks, I’m often asked for my opinion on the future of IT in general, and security and networking in particular. Invariably the conversation will shift towards a new networking technology or the response to the latest security threat. In truth, I think the future of firewall lays in solving an issue we started to address in the past.

FireWall-1, the name of Check Point’s flagship firewall, is a curious name for a product. The product that’s become synonymous with firewalls wasn’t the first firewall. The category already existed when I invented the name and saved that first project file (A Yacc grammar file for the stateful inspection compiler, if you must know.) In fact, one of the first things Gil did when we started our market research for Check Point in 1992 was to subscribe to a newly formed firewall-mailing-list for, well, firewall administrators.

But FireWall-1 was the first firewall to make network security simple. It’s the stroke of simplicity that made FireWall-1. From software to appliances, firewall evolution has largely been catalyzed by simplicity. It’s this same dynamic that three years ago propelled Gur Shatz and me to start Cato Network and capitalize on the next firewall age, the shift to the cloud.

To better understand why simplicity is so instrumental, join me on a personal 25-year journey of the firewall. You’ll learn some little-known security trivia and develop a better picture of where the firewall, and your security infrastructure, is headed.

The Software Age & Simplicity Revolution

When we started developing FireWall-1, the existing firewalls were complicated beasts. Solutions, such as Raptor Firewall or Trusted Information Systems Firewall Toolkit (FWTK) relied on heavy professional services. Both came out of corporate America (If I remember correctly Raptor from DuPont and FWTK from Digital).

The products required on going attention. Using new internet applications could mean installing a new proxy server on the firewall. Upgrading an existing application could require simultaneously upgrading the existing proxy servers, or risk breaking the application. No surprise, the solutions were sold to large organizations willing to pay for the extensive customization and professional services required to implement and maintain them.

They say “necessity is the mother of invention” and that was certainly the case for Gil, Marius, and I. We were anything but corporate America. Extensive on-site support, custom implementations, professional services — the normative models wouldn’t work for us sitting in my grandmother’s apartment 10,000 miles away from the market, suffering the sweltering Israeli summer with no air conditioning and only $300,000 in the company bank account.

We needed a different strategy. What we needed was a solution that would be:

- Simple to use without customer support,

- Simple to deploy without professional services,

- Simple to buy from a far, and, above all,

- Simple enough for three capable developers to build before running out of budget (about 12 months).

To make the firewall simple to use, two elements were key:

- A stateful and universal inspection machine that could handle any application given the right, light-weight configuration file. No longer was there a need to deploy and update custom proxy servers for each application. In the coming years, when Internet traffic patterns changed to include an ever growing number of applications, stateful inspection became critical.

- An intuitive graphical user interface that any sys admin could understand and use almost immediately.

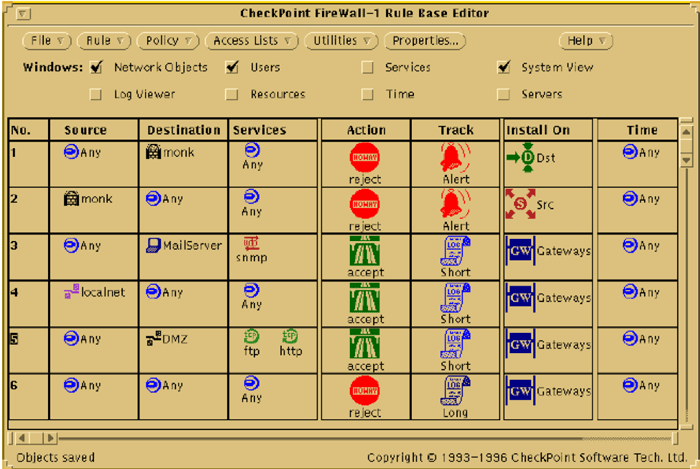

Actually, we didn’t get the UI right the first time around. After a few months of development, we ran a "focus group” with friends that luckily were PC developers. During those days, PC developers were much more advanced UI folk than us Sun Workstation guys. Our focus group hated the UI, which led us to start all over, and develop a PC-like interface that looked like this:

Caption: A screenshot of FireWall-1’s early interface.

I still think it’s pretty great. By the way, you might notice a host called “Monk” in the rule base. It was one of the two Sun workstations we owned (actually borrowed as a favor from the Israeli distributor of Sun), and named Monk after Thelonious Monk, the American jazz pianist and composer. The other machine was named Dylan. And all of those cool Icons? They were drawn by Marius who doubled as our graphic artist. He worked on a PC.

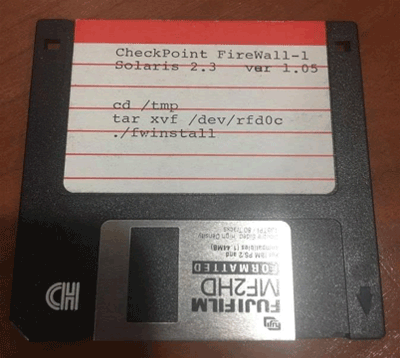

To make the product simple to deploy, we made a special effort to compress the entire distribution into a single diskette with the install manual printed on the diskette’s label:

Caption: An early FireWall-1 disk. Note the installation instructions on the label.

The last critical point was making the product simple to buy. In a world where the competition sold direct and made a considerable part of their revenues off of professional services, we decided to become a pure channel company and sell exclusively through partners.

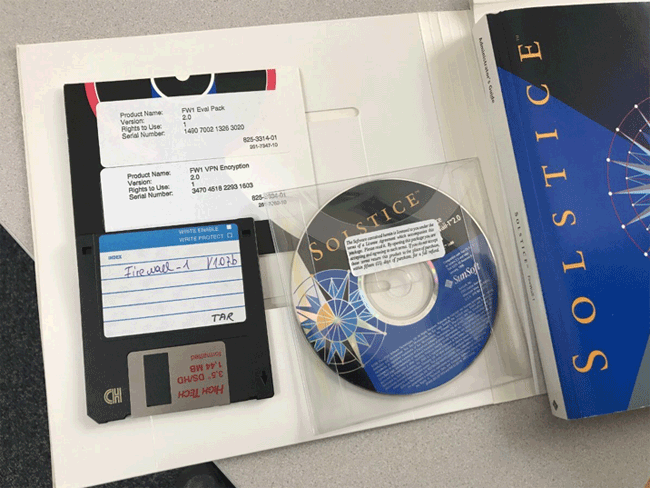

We were very lucky to sign up early on with SunSoft, the software arm of the then leading computer manufacturer, Sun Microsystems, and become part of their popular Solstice suite. Sun's distribution know-how and capabilities were critical in the early days. In the pull market that followed, the fact that buying FW-1 through our partners was simple became critical.

Caption: An early FireWall-1 disk packaged as part of Sun’s Solstice suite

The Appliance Age: Simplicity At Scale

As firewalls became increasingly popular, the workstation form factor became increasingly difficult to maintain. The basic premises of our business — simple to buy, simple to deploy simple to use — were eroding because of how customers were using the product. It's one thing when you have a single Internet control point running on a repurposed workstation, but now organizations had distributed hundreds of these firewalls running on all sorts of machines and operating systems. You can imagine the mess.

Moving from shrink-wrapped software to prepackaged appliances seemed like, well, a simple, logical next step. The transition was anything but simple.

There was an existing, perimeter appliance already in the market — the router. It made perfect sense to embed the firewall in that appliance, at least that's what I thought when I signed an OEM agreement with Wellfleet Communications, the then number two router company (after Cisco, of course). We even had a customer with an amazing 300-node purchase (a large Fl in NY). One of our leading engineers, Nir Zuk, relocated to Boston to work at the Wellfleet office and support that project.

Caption: Embedding the firewall in a Welfleet router was good in concept but the remained crippled by limitations of the underlying router.

I remember the day I visited Nir. He wasn't happy at all, spitting and cursing as only Nir can. The hardware and operating system underlying the Wellfleet router were not strong enough nor dynamic enough to address the needs of a sophisticated firewall. It was a far cry from developing for the Solaris-based workstation. Work progressed slowly and, in the end, Nir was talented enough to get something basic working, enabling us to implement the 300 router- firewall nodes purchased by the customer. But the product remained crippled by the underlying platform. Overall, the product wasn't a success.

It became clear that there was a need for a dedicated appliance, and so we started looking around for a platform flexible enough to run a firewall. One of the early platforms we targeted was an appliance from a company called Armon, who ran a network monitoring solution based on the RMON standard.

Since the appliance was built to run sophisticated software we believed it will be a good match for FW-1. The Armon CEO, Yigal Yaakobi, was a big enthusiast of the OEM model, and licensed the box to us to build a dedicated firewall appliance. But Armon was just bought by SynOptics Communications, the then leading wiring hub manufacturer, who merged with Wellfleet to form Bay Networks. We needed Bay Networks management buy-in, which meant meeting with Jim Goetz, later the famed investor with Sequoia.

Yigal and I dressed up in our best, and in my case the only, suit and met Jim at a café shop in Vegas across from the Interop show. The meeting was not a success. Apparently, Jim did not appreciate my style in clothing and spent most of the meeting scolding it. And so the future of the firewall suffered a minor setback due to my lack of fashion sense. But the idea apparently stuck, because we will soon meet Jim in a more fortunate circumstance.

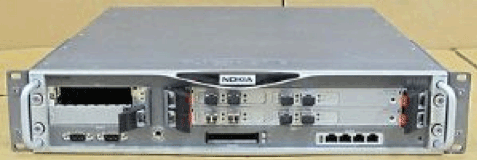

Caption: Embedding the firewall in Nokia appliances (pictured is a Nokia IP1220) proved successful.

Anyway, I did not give up. I hired Asheem Chandna (later the famed investor with Greylock) as the vice president of business development and product management, and relocated Nir Zuk to the Bay Area. The two started, among other things, the OEM program for Check Point that yielded the very successful Nokia relationship, which for many years was the basis of Check Point’s line of appliances.

As an epilog, Nir, Jim and Asheem started a company few years later called Palo Alto Networks that redefined the network security market, introducing the first modern unified threat protection appliance. And, yes, it was simple to buy, deploy and use, and wonderfully addressed the challenges of the changing traffic patterns it needed to protect.

Caption: Palo Alto redefined the network security market with unified threat protection appliances (shown here is a PA-7000 series appliance)

The Cloud Service: Simplicity For Today’s Business

Firewalls were always in the business of defining the perimeter, but originally we had ambitions to go after the business of the WAN. At Check Point we developed VPN-1 immediately after releasing FireWall-1 (and then merged them into one product suite), the first IPsec-based VPN between gateways and later a client VPN version as well for remote users. The idea was to replace Frame Relay and ATM, the predecessors of MPLS.

Caption: An early VPN-1 disk for running on a Nokia appliance

Then we developed FloodGate-1 to provide WAN optimization and QOS for the IP VPN network. The goal was to create a platform for a high-quality, Internet-based WAN that did not require dedicated, expensive, Frame Relay, or ATM connections and would extend beyond physical locations to any type of nomadic (if we use the ‘90s term) user.

It failed. MPLS won. People wanted SLA-backed networks to run their mission-critical apps. The Internet was too unpredictable. That was my exit project at Check Point. After I left, the FloodGate-1 effort was sidelined.

I also put this problem aside and started working on bringing firewalls deep into the datacenter of organizations. That took about 12 years and yielded other companies called Imperva and then Incapsula, founded by Gur Shatz, who soon emerged as a true cloud innovator.

In Incapsula, for the first time, the appliance form factor came under attack. The datacenter was by now mostly hosted on a cloud service or even just a good, old, plain hoster. Physical appliances made little sense when you could use a third-party cloud service. Incapsula was a great success (still is) because it took application delivery and security, and matched the cloud challenge with a cloud toolset.

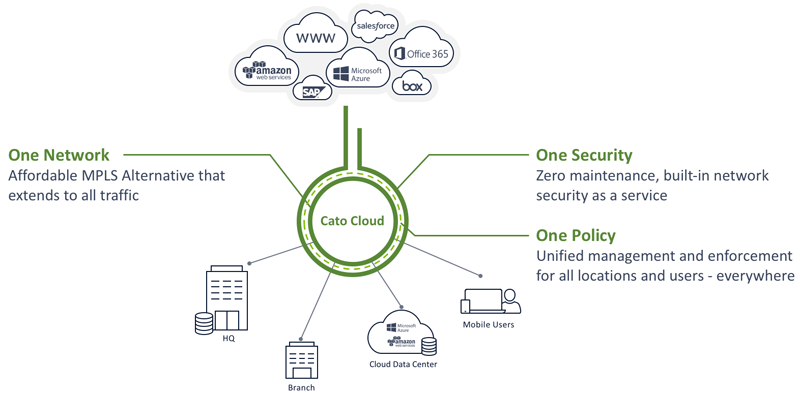

While we were busy with the datacenter firewall it became increasingly clear that the perimeter was dissolving. In a world where most of my apps are third-party Software as a Service (SaaS), most of my data resides on third-party, public clouds, and most of my work is done on mobile devices out of the office, of what use are physical appliances when they’re guarding my now largely empty office?

Organizations had to buy increasing number of products for protecting their SaaS applications, Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) cloud datacenters, and mobile users on top of their ongoing firewall spend. To make things worse, lots of branch locations and small offices that never had a direct breakout to the Internet but just backhaul over MPLS to company center where the firewall resided could not do that anymore. The Internet became a utility. You needed it anywhere, anytime, lots of it and in a secure way. So, all sort of patches like MPLS augmentation and secure web gateways emerged to increase Internet availability to all elements of the organization. Things were very messy at this stage. A far cry from the simple to buy, deploy, and use idea of the past.

Caption: With cloud, you can create one network with one set of security policies for all locations, resources, and users

When Gur (yep, that guy from Incapsula fame) and I started Cato Networks almost three years ago we realized the problem of WAN and perimeter are interlocked and require a new architecture that will make secure Internet and WAN available everywhere, anytime to any part of the organization – a branch office, a data center, a cloud segment, a mobile user. It was like going back 17 years in time to the days of VPN-1 and Floodgate-1 and taking a round two at that problem, but this time in a completely different world driven by cloud and mobility. The key remained the same: bring simplicity to an increasingly complex world.

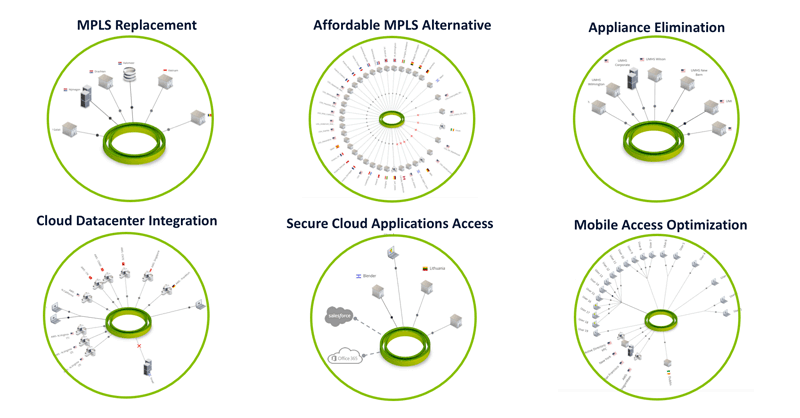

Caption: Cato addresses a diverse range of use cases.

Following the Incapsula playbook we built a cloud network able to deliver anytime anywhere networking and security services. Think AWS for networking and network security. I believe this is the architecture that 10 years from now will dominate the enterprise WAN.

But it’s not just my belief. After 18 months in the market, hundreds of customers with thousands of branch locations across all verticals now rely on Cato Cloud to connect and secure their corporate networks. They agree with us: Cato is the future of networking.

Your IP address:

3.149.27.97

Wi-Fi Key Generator

Follow Firewall.cx

Cisco Password Crack

Decrypt Cisco Type-7 Passwords on the fly!